POLEMIC

TOWARD THE LIBERATI NG

CRITERIA OF ART

(part1 of 2)

At 10 o’clock on any day of the week except legal

holidays, the typical art museum anywhere in the country is open for visitors.

The entrance hall usually leads the average aficionado of art through a series of

galleries in orderly progression from one imposing collection to another,

presenting the visual history of civilization, the drama of the human mind. As

far back as man could reason, his works are there: evidence of the Neolithic,

the dawn of civilizations, the antique remains of dynastic power, the classical

traditions, the intervening lines of humanist development, the Renaissance and

Baroque flowering, to the most recent acquisitions of modern and contemporary

art; they are all there, more or less, in periodic array.

As he progresses leisurely through

the halls, the visitor is led through a process of transitions in the ages of

man. He is hardly aware of the changes, yet their impact, gradual and moving,

is not lost on him. He correlates the concrete visions of the past into a

stirring processional of events.

As he reaches the modern age, his

eye is delighted with the radiance, the luminosity and joy of impressionism.

Yet he is vaguely disturbed by its unmannerly sketchy appearance, its random

spontaneity, its lack of finish, its seeming amateurishness.

Then, as he crosses the threshold to

the new art, to postimpressionism and beyond, deep into cubism, expressionism,

abstraction, and surrealism-their derivations and deviations the alarm bells

begin to ring in his head, the sirens and the fireworks go off, and our

aficionado of art-who is not a snob, by the way- is left in a morass of

helpless confusion and dismay. The even tenor of his mood is disrupted in the

colorific visual violence, the aesthetic assault from the walls. The simple

progression is gone; the contact with life is demolished in a pyrotechnic

profusion of unrecognizable fulminations.

In the art of the past, there seemed

to be no line of visual expression our visitor to the museum could not follow.

No matter how far back, even to Palaeolithic cave art, he could trace the

thread, the primitive urge, the historic need, the humankind. At times, the

line stretched thin and tenuous; at others, strong and firm. But always it was

there for him to see, a long unbroken line of human succession, linking a vast

reach of time, twenty thousand years of change. Now in his own time, in the day

when the visitor and modern man have arrived at a new age of invention and discovery,

recognizing the demand of every human need and the promised fulfilment of every

human dream, the historic line of art communication in human understanding,

imperative now more than ever before, has broken down. The new art that

thundered down at our receptive visitor to the museum is filled with an

eclectic diversity of forms-biomorphic, kinemorphic, psychomorphic, mechanomorphic-all

of them intensely personal, subjective expressions of inner states of being.

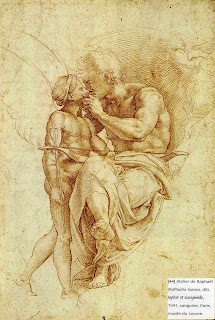

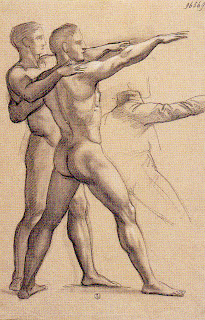

The figure in art, the highest expression of man's visual creative powers, the

subject of twenty thousand years of painstaking search, has been reduced to a

number, a cipher, an esoteric symbol, a kinesthetic impulse driven by a

primitive-emotional urge. Today, the anatomical man, for all artistic purposes,

is dead.

Art, in the mid-twentieth century,

is in a period of critical transition. We are seeing today an extraordinary

concentration of effort and energy in the visual arts never before experienced

at any time in history. Never has there been so widespread an interest, never have

so many individuals participated actively in its creation. Never have we had so

much contact with art of all kinds-art from the dim reaches of time, art from across

the oceans, art of primitive peoples; art from the past great eras to the

modern era; fine art, commercial art, industrial art, technical art,

experimental art, psychological art, leisure art, amateur art. It would appear

we are seeing a great new Renaissance in visual art, for in the volume of art

creation we are witnessing a cultural phenomenon of the first magnitude.

In the frontiers of knowledge and

culture, art may be said to be in its heyday of exploration. The exploratory fervour

of the sixteenth century, using new logic, new mathematics, new science, opened

the unknown areas of the world to commerce and physical contact of peoples and

brought out a treasure of artworks to the Western world, which only now, in the

twentieth century, is being experienced by artists in our time. Like the riches

of the East in an earlier day, this influx of art is beginning to be seen,

felt, and assimilated. The day of global exploration is accomplished. Now has

begun the day of cultural exploration, some five hundred years later. Yet never

has there been so much confusion in the arts as there is today.

The twentieth-century artist appears

to be in a state of conflict and disorder. He has a world of art to explore,

yet he shows no purpose, no goals. He seems to have lost his sense of direction

as he ranges across the uncharted art frontiers. He has rejected the compass; he

has thrust aside standards, criteria, definitions; he has renounced science as

a tool in the discovery and development of art. He has rejected the human need

to relate, to communicate the results of discovery.

If we recognize it is the mission of

science to define with clarity and precision the workings of the universe, to

relate with order and harmony the new concepts of time, space, and energy into

new and better ways of life, we reach the conclusion that science is the most

powerful instrumentality in the progress of man. To the artist, however,

science is considered an invasion, a hindrance, a stricture upon his free and

personal interpretation of the world. He sees the scientist as an intellectual

instrument-precise, logical, mathematical, mechanical. He sees himself as a

sensitive organ of feeling, emotion, inspiration, and intuition. As a result,

the artist rejects science and scientific thinking in the projection of art.

Art to be pure, he reasons, must be devoid of science; feeling is not precise; emotion

is not mechanical; inspiration is not logical; intuition is not measurable-the artist

is no scientist. Attempting to distinguish the work of art from other works of

life as a refinement of cultural endeavour, distinct and separate from the

ordinary and commonplace necessities, the artist has in effect said that

science prods and pushes with the workaday things to build a better mousetrap,

while he, the emotionally endowed aesthete, represents the inspiration at work,

the filtered aesthetic reflex of society, the fine arts. It is a neat trick of

turning the tables; the bohemian wastrel and garret outcast, through

intellectual legerdemain and bootstrap levitation, has become an individual of

a pure kind. In this state, he raises above plebeian strivings to a position of

sophisticated recognition and social grandeur, and from this remote pinnacle

surveys the marketplace mediocrity below.

How devastating and destructive a

view this is can be gauged by the fact that in every other area of modern life,

in every field of endeavour, science merges easily, compatibly,

productively-except in the visual arts. Only here is the view held- by artists

of all idioms, indeed, the whole of contemporary society-that science and art

do not mix, that they are mutually contradictious, irreconcilable. Yet this is a

distortion of the truth, a delusion, a self-imposed deception, a retreat from

life.

The dislocation of art and science

has never been so apparent as it is today, almost a hundred years from the time

it first revealed a disturbance in the continuity of art communication. The

impressionist rebellion, the last flower of the humanist spirit of the Renaissance,

still exhibiting its attachment to scientific precepts in its spectral light

and its recorded observations of the momentary life of the people, their work,

recreation, and leisure, was too weak a movement to triumph over the entrenched

authority of the regressive French Academy. When it withered and died after twenty

years of frustration and social exile, the deep space of the picture plane

became a barren shell; the landscape closed down into a two-dimensional

decorative pattern of shapes; the vibrant pulsating figure, the human analogue,

shrank and hardened in to an artefact, a constructed intellectual object; the

artist's emotional power and insight in human affairs subsided into symbolic

outcroppings of tenuous moments of excitation, apprehension, or despair.

In their seizure upon the

"immediate" and the "personal," the followers after the

impressionists disengaged themselves from every known principle of spatial

structure and design. They withdrew from earlier concepts of form, value, color,

and image. They worked toward the total rejection of the Academy. In their

hatred of the "academic," they extirpated the scientific legacy of

art, carefully nurtured and marshalled over fifty centuries of historic development,

and erased it in a short span of fifty years. In their need to rebel against

the "academic", they rebelled against science. They proclaimed the

distinction of the "fine arts" and gave it to society as a new

description, uniquely different from academic art or the utilitarian commercial

art. They presented to the entire contemporary generation of society and the

artists who followed the doctrine that "art" was above scientific discipline,

above definitions and criteria. The need to communicate in art, to be responsible

for the exchange of art experience in to human experience, was considered to be

an anachronistic demand of aggressive academic vulgarity, and was held beneath

contempt.

The rebellion against the

"sterile", the "mechanical," the "academic"-truly

a human cry of anguish- had become a distortion and a delusion. The fine artist

had turned his back on reality. He became an incoherent high priest of good

taste, an absolute arbiter of egocentric mirror-image art, a melancholy,

involuted microcosm turned in upon itself to an inevitable dead end.

Yet the impulse to art is

unquestionably the impulse to life. The art process and the life process are an

indissoluble entity. The components of one are the components of the other.

They may be uneven, but never alien; they may be out of joint, but never out of

union.

The need to create, to synthesize

experience, is a primal force in art. Because it is the distilled essence of

perception and experience, art needs its adherence to life. But the work of art

of today needs, more than ever before, the energizing transfusion of commonly shared

experiences. It needs a conscious agreement with the cross-fertilizing, wider empirical

objective.

Artists of today stand at the

crossroads of immense opportunities and possibilities.

What they have discarded earlier in

the scientific discipline of art as academic, inhibitory, and repressive of

free expression they now substitute, strangely, with new science! In their

search for a new basis of art without restraints, they lay hold on the world's

storehouse of art, which they now have a t their command. They feel the impact of

new scientific fields and attempt to resolve these in visual terms. Virtually

the entire gamut of human and social discovery, scientific and technical

advances have found their place in the free interplay of the design structure.

Never in the entire history of art have so many variations of art expression

occurred in a single given era. The range of concepts and movements is truly enormous;

even as this is being written, new ones are being born. The listing of a few at

random is to indicate the multiplicity of reactions to the technical-scientific-analytical

age.

Thus, starling with impressionism,

we have: pointillism, neoimpressionism, postimpressionism, fauvism, cubism

(analytical and synthetic), expressionism (three schools, perhaps more), Orphism,

surrealism, abstraction, Dadaism, futurism, nonobjectivism, neoplasticism, constructivism

, purism, Bauhaus, primitivism, social realism,

dynamism, abstract expressionism,

abstract surrealism, mobiles, stabiles- and on and

on, et cetera.

The list seems endless. In these

definitions can be seen some of the descriptive leads to the larger environment

of the age, where the art form has attempted to embrace psychology and

psychoanalysis, natural history, biology, chemistry, physics, kinetics,

mechanics, engineering, archaeology, anthropology, microscopy, telescopy, etc.

In the fission and fusion of two-dimensional space, the artist uses science

pragmatically, experientially, without whole concepts. Nevertheless, it forms

the basis of his art. But it is not a complete art. For, in the practice of it,

the artist simultaneously rejects the existence and influence of any scientific

rigor, control, criterion, or standard. His art, perforce, without objective

direction, releases a welter of exquisitely personal, eclectic minutiae.

If we quickly scan the art horizon

and examine the amazing output of art today, we find endless experiments in

textures; inconclusive shapes, masses, forms; positive and negative space;

tensions of line and mass; contrasts in color; line variations; eclectic

working together of art old and new; cell structure; automatic writing-endless,

precious, purist variations, powerless to come to grips with itself, to

proclaim any direction or value judgement for others. The figure in art-always

the touchstone of the art of any era-has become the visual admission of the

artist's failure to cope with the ethical-moral, social-human needs of our

time. It is a symbol of dislocation and depersonalization; the ideograph of the

alienated man, insecure, lonely, without fiber; the portrait of the artist, the

autograph of the author.

Probably the most disturbing

phenomenon in the art of the current century, a result of the dislocation in

the dualism of art and science, is the profoundly pervasive indifference of the

whole contemporary generation of artists to formulate a clear-cut definition of

art itself. The obscurantism, the evasive arguments and denials, the lack of

any direct, forthright statement, is evidence of a deep-going crisis in art. With

the exception of a few scholars, nowhere in the field of art has there appeared

a challenging assertion to say what art is in our time.

In the social arena of modern living,

the most engaging diversion is the extensive practice of generalized and

personal analysis. Because we live in a technical scientific-analytical age of

calculating machines and statistical truths, we respond to the powerful

pressures of analytical behaviour-to define, to clarify, to identify. It is a

great game of analysis; dissection and decortication of the underlying

mechanisms in every segment of the social structure, from psychoanalys is to

social surgery. We practice the analytical game everywhere except in the fine

arts. Here, in the arts, the emotional fog rolls in , intellectual inertia

overtakes us, and the cultural swamp remains undefined, unexplored.

Words like style and taste have no

clear meaning except, perhaps, in commercial usage. And the special caste

terminology- feeling, intuition, inspiration, perception, creativity--are

ritualistic ceremonial expressions of artists, undefiled by simple definitions except

in the laboratories of clinical psychologists.