The special word art is a sacred

temple, a mysterious inner sanctum of artistic pursuit, where magical

intellectual powers interact with primordial outpourings of the irrational subconscious.

Paraphrasing Thucydides, who has put it abruptly: When common, everyday words

lose their definitions and meanings, there is a general crisis in a given

field.

To go further, when art terminology

has lost its power to convey sense, idea, or meaning of art expression, then

the artist, the art field, the whole cultural endeavor, is conflicted, confused,

and disordered; it becomes a chaotic wasteland, a lost continent of the

culture.

The net result has been to let loose

a carnival of art dilettantism and chi-chi art sophistication concealed behind

an imposing front of synthetic rhetoric, aesthetic lyricism, and emotional

bathos. The state of art today is such that it can now be performed by tyros and

amateurs with virtually no study, preparation, or training. In galleries and

exhibitions, the amateur aesthete can now compete on equal terms with the

seasoned, knowledgeable master with such facility that hardly anyone,

frequently not even art connoisseurs and critics, can tell good art from bad art,

amateur art from professional art. When the quest for brevity and simplicity

has been reduced to infantile primitivism, we have lost the validity of concepts;

when the creative urge to reveal life has been distorted into a wayward surge

of undirected energy, we have lost control of direction and experimentation;

when the search for clarity and order has been diverted to piecing out a

meaningless jargon of amateur misbehaviour, we have lost our artistic heritage;

when the need for definitions, standards, and criteria has been seduced by

vacuous emotional mumblings, we have seen the perversion of the philosophy of

art and aesthetics. When the artist has surrendered his status, his authority,

his principles, his professionalism, then the amateur has taken over, and the jungle

is upon us.

The problem of the amateur in art is

really the problem of the artist in society.

To say that the amateur has invaded

the arts, and that the fine arts are becoming an amateur art, is to say that

the artist has defaulted in his obligation to the social environment.

But this view alone does not face

the issue squarely, for it would force the conclusion that the artist alone is

responsible for the neglect and deterioration of art. To say that the artist has

rejected the norms of living, has removed himself from society, has turned away

from reality to promote his inner personal image of life and art-for-art's-sake

isolationism, is to say the exile prefers the desert, the suicide enjoys

cutting his veins, the tortured man relishes his anguished cries for help. In

truth, these are but the pathetic attempts of the withered, truncated man to

become a whole man. The issue at hand is really a dual problem; it is not only

the artist's inbreeding and involution-it is also society's forced estrangement

and neglect of the artist. If there is a crisis in art, a disintegration of its

moral fiber, a decay of its historical precepts and philosophical virtues, it

is because society first has disavowed and disabled it as an intellectual

resource, a cultural necessity, a social and educative force. It has refused

its permission to be integrated with the technological, scientific advances in

our time, except as a utilitarian, commercial, ancillary art. To engage a

solution on this basis needs a moral reawakening of society and a conceptual

reworking of art.

The reestablishment of self-control

in the artist and social respect for art devolves on creating again a new

dualism of art and science in the twentieth century. The obscure terminology

must be clarified and attached to commonly shared associations; personal values

must be defined according to generalized experience; the personal subjective purpose

must be widened to embrace the broader social goal. The immediate and urgent necessity,

the first order of the day, is to redefine the old word art. The clichés, the nonsense, must be stripped off. Art must have

a new interpretation, infused with new meanings and values, in order to find

its equal place with other positive cultural pursuits in our time. It must mean

as much to the population as medicine, surgery, bacteriology or physics,

engineering, architecture-or steak, mashed potatoes, apple pie. It must be executed

so ably and understood so well that it will stand strong and firm as a

skyscraper

does when it is done well-or it will

collapse in ruins when it is not. Art must be refined into a critical

intellectual tool to meet these challenges. New cutting edges must be given to

the old "saw," fine-honed and sharp, diamond-hard and tough , to

stand up under the friction and abrasion of life. To be "art," it

should be made responsible for communication of its ideas and concepts; it

should reflect the life and times of the artist, his integrity, his ethics, his

democratic ideals in the progress of man; it should show his developed skill

and judgment in projecting significant, expressive form; it should reveal

invention and originality in transmitting the aesthetic experience; and, above

all , it should arise out of the environment, the social-human-scientific

culture base as the controlling factor in its creation.

This does not mean that strictures

or rigid conventions must be placed on the artist; nor does it say that

experimentation or freedom in personal expression should be curtailed or

abrogated; nor does it propose that there is only one way of seeing the world around

us, one outlook, one style or method of approach. It does not ask the artist to

obey or be subservient to any fixed rule, regulation, dogma, or tradition. It

does not set up absolutes of authority, or impose conditioned reflexes of

conformism. However, it does ask the artist to respect and rely on the positive

norms, values, and traditions that still operate and still function in the

study and preparation of the artist, that still apply in the cultural background

of modern art creation. These should be seen as the educative resource, the imperative

precondition for the survival and growth of art.

Socrates, we are told, attempting to

probe into the nature of law, speaks of the laws of men as a response to the

social pressures that arise out of human conditions in the natural environment.

And therefore, he argues with penetrating insight, to understand the nature of

law we must first understand the law of nature. The liberating principle of art

lies precisely here, in the Socratic approach to the conjoined relationship of two

mutually attracted, interacting forces-man and nature, nature and man. This

synergistic principle, if we can refer to it as such, argues for a relationship

of ideas, in Toynbee's words, in a context of challenge and response, response

and challenge. It seizes upon diverse attitudes of thought, probing for

intrinsic attributes of contraction and expansion, refinement and extension; it

enlarges the field of intellectual vision, and refines the area of critical

judgment; it tends to limit subjective bias and mental myopia.

If we apply the principle to one of

the central problems of art, the presence of the amateur in the fine arts, we

might uncover these provocative correlations: To understand the amateur of art,

we must first understand the art of the amateur; to recognize the professional

of art, we must recognize the art of the professional; to explain the presence of

the amateur in professional art, we must explain the presence of the

professional in amateur art. Suddenly, the critical questions rise to the

surface: In how many ways is professional art an amateur art? Can professional

art be easily imitated by the amateur?

The way is open for other

challenging assertions. For instance, that much-abused old habit, skill: To

discover the skill in art, let us first discover the art in skill. Or: To ask

where the old traditions are in modern art, we must first ask where the modern

is in the old art. This is not a mere game of idea inversions or word juggling.

If it were, the new statement of ideas in reverse would not be so sticky with

uneasy, astringent meanings that quickly leap to mind. Nor is this a conclusive

demonstration posed as an answer to the problems of art. It is an exercise of

reason, an analytical approach in the examination of hitherto unassailable

notions. It might be seen as the first incision in cliché and slogan surgery to

arrest the deterioration in art.

A new dualism of art and science, if

we can agree on the premise as indispensable to art today (as it was in the

Renaissance), must again seek to introduce commonly understood criteria and

standards. We must re-establish certain major links with the past as historical

background, consistent with art progress today. We must incorporate the old traditions

that are still viable, still alive today. But which are the living traditions

and how can we be sure? Let us apply the synergistic principle and make an

incision.

Our civilization is predominantly an

advanced technical age of science. It developed its abundant greatness from

earlier civilizations and beginnings. Now, a question: Where do the earlier

civilizations appear in the modern age of science? We must first ask, where

does the modern age of science appear in earlier civilizations? The answer

seems clear: in those civilizations that have made scientific contributions.

The reason we search out the older civilizations, and attach their findings to

ours, is a scientific reason. This is true historically for our humanist-democratic

institutions as well.

Therefore, the answer to the older

traditions in modern art lies in the context of the larger framework; those old

art traditions that tend to live on have survived for a humanist-democratic scientific

reason.

Where modern art has precisely been

interested in the art of the world's cultures, across the seas and in the past,

is the human reason, the scientific reason. But it has done this willy-nilly,

capriciously, driven by impulse rather than direction. It has chosen, through

uncritical acceptance of the nineteenth-century artists' hostility and rage

against the anti-libertarian French Academy

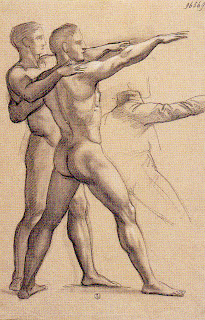

Because this polemic underscores the

need to return to rational definitions of the entire nomenclature of art and

the reworking of substantive new standards, the return of the human anatomical

figure to the lexicon of art is a major condition toward the establishment of a

new dualism of art and science. The premise of the human figure does not propose

a restatement of medical anatomy. To rediscover Vesalius is no

twentieth-century triumph; Vesalian anatomy must be given back to Vesalius. An

advance in anatomy for art must be made in artistic anatomy. Muscle and bone

structure must be left off where they inhibit or destroy understanding of

surface form, artistic and expressive form. The anatomical figure of art must

make a contribution to the dynamics of the living figure, of interrelationship

of masses in motion, of insights into the figure to be used by artists and students

of art, not medical students and surgeons. Because life today is so complex and

varied, multiplying its dimensions with every passing day, the sincere,

creative artist must be quick to react with keen insight and increased

awareness to the changing profile of contemporary life. Because he must show

versatility, flexibility, and diversification in experimental behavior, he must

base himself securely on the human root, the warm kinship of his scientific

brother, the consanguine association with the larger social environment.